your journey

What does it take to foster innovation?

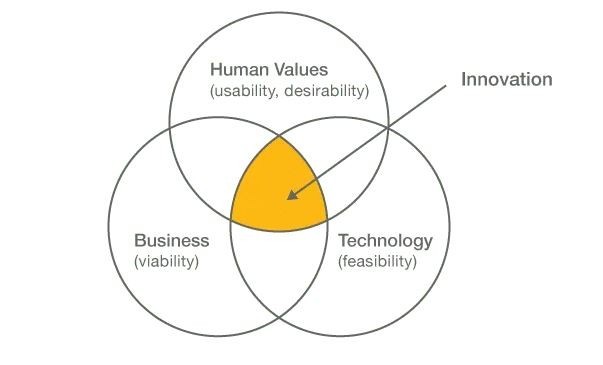

We like to think of innovation as being at the confluence of technical feasibility, business viability and human values.

While most organisations possess the business knowledge and technical skills to execute and produce incremental innovations, we’ve learned through our work that many still lack the human component. That is the value of design: it brings people into the equation by listening to and empathizing with them. A culture of design improves organisational capacity to find the right problems (as opposed to just problem solving) and spurs creativity; it is the secret to reliably generating innovations previously out of mind and out of reach.

There are several foundational “micro-elements” we’ve identified as being necessary to foster design-led cultures of innovation, but it boils down to three pillars: people, process, and place.

People

The first pillar refers to having people with the right skill sets and mindset in the organization.

To make design effective, organizations need people with the right skillsets. That means designers who know how to generate ideas and how to turn them into realities; designers who can do user research and know how to use the latest software to create wireframes.

In addition to an adequate design skillset, individuals throughout the company need to strive towards embracing a design mind-set. A Fast Company Article, called 4 Myths About Apple Design, From An Ex-Apple Designer, said that the secret to its success is not that Apple has the most designers or best designers, but the fact that the entire organization has a design mind-set. It is not one or the other, but both.

“It’s actually the engineering culture, and the way the organization is structured to appreciate and support design. Everybody there is thinking about UX and design, not just the designers. And that’s what makes everything about the product so much better . . . much more than any individual designer or design team.”

However, before an organization sets out to be more design-centric and innovative, there must be executive support to enable the necessary changes. Innovation is bottom up, middle out, and top down, but backing from the decision makers is necessary before everything else can fall into place.

Process

The second pillar refers to having processes in place that support innovation rather than impede it. It needs to start with empathy and include cross functional collaboration, prototyping, and fast iterations based on feedback from real users. These processes frame failure as an opportunity to learn rather than something to avoid. For example, a waterfall process that follows a strictly linear process, in which communication happens via specification documents passed between teams, could miss opportunities for innovation. Furthermore, new discoveries, and insights gathered at later stages of the project could be considered a failure on the part of the teams working in the early stages.

But we think of process as something beyond individual projects. These design principles can—and should—be applied at a much larger scale, touching all parts of the organization at every level.

The third and final pillar, place, refers to open, inspiring work spaces—both physical and virtual—that facilitate collaboration and celebrate creativity.

Place

The third and final pillar, place, refers to open, inspiring work spaces—both physical and virtual—that facilitate collaboration and celebrate creativity.

The architecture and design of the places in which we work influence how we behave in them. Siloed offices tell occupants to “be efficient”, whereas open floor plans with places to brainstorm ideas and plenty of common areas for meeting and mingling tell occupants to “be creative” and “collaborate”. Places can break down hierarchies and make connections with people from diverse disciplines—a type of radical collaboration is essential to innovation. Since collaboration increasingly happens virtually, organizations need the tools to make the best of this way of working together.

People, process, and place are all important in their own ways, but it is the interplay between all three that is the catalyst to fostering a design-led innovation culture. After all, talented designers will not be as impactful if using a process that excludes end users, and well-designed collaborative spaces that lack people with the right skill set or process know-how will not be fully utilized. When they develop in conjunction with each other, the three pillars add up to something greater than the sum of their parts, and innovation becomes the natural output.

Share this:

Neil ran his first SAP transformation programme in his early twenties. He spent the next 21 years working both client side and for various consultancies running numerous SAP programmes. After successfully completing over 15 full lifecycles he took a senior leadership/board position and his work moved onto creating the same success for others.